The one thing travellers expect from a beautiful beach holiday is a beautiful beach. Clean sand, clear water, abundant sea life and a general respect for the beauty that nature has bestowed. You don’t always get it. I’ve picked up endless plastic bottles abandoned on beaches in various countries, despaired at high tidemarks littered with junk, picked beer cans out of coral reefs, and peered into murky, oily water wondering what, if anything, can survive down there. Humans really are relentless in our ability to stuff up paradise. Then you get the Seychelles, a scattering of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean, where mankind finally seems to be on nature’s side.

Words & pics Lesley Stones

The islands feel far more pristine and unexploited than many other countries. Perhaps that’s partly because they’re made of granite, with narrow roads that twist through hairpin bends to cross the mountainous interiors. Spectacular, but not conducive to farming or industrialisation. So nature and its lure for tourists is pretty much what keeps the economy afloat, and the islanders are determined to protect it.

The results are obvious. One day I took a 2km hike through Morne Seychellois National Park on Mahé island to Anse Major beach. It’s stunning, and almost completely deserted because you can only get there by hiking or by boat. The snorkelling was fabulous, and I almost choked with laughter when I was magically swirled up in a shoal of hundreds of silver, shimmering fish.

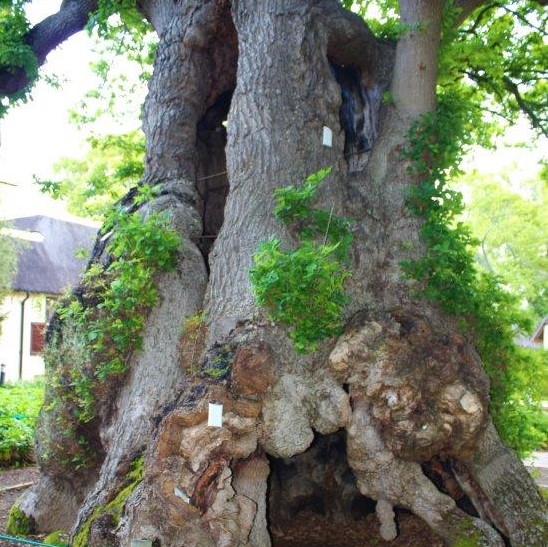

While you might think that Madagascar has the monopoly on bizarre endemic animals thanks to the DreamWorks movies, the Seychelles aren’t short of quirky specialities either. One is the Aldabra giant tortoise, and I spent ages feeding some in Mahé’s Botanical Gardens, dodging their massive feet as they jostled each other to chomp the leaves I enticed them with.

Another endemic novelty is the Coco de Mer, a palm tree with male and female versions. The female produces giant nuts that resemble the female pelvis, and it’s such a rarity that there’s a lucrative poaching and smuggling scene. This cheeky palm tree inspired the lovely bum-shaped stamp that immigration officials bang in your passport when you enter the country.

Island-hopping is the best way to experience the Seychelles, and from Mahé you can easily reach Praslin by ferry or a 20-minute flight over the brilliant turquoise waters. Much of Praslin is devoted to the Vallée de Mai nature reserve, and from there it’s a short ferry trip to La Digue, where everyone tootles around on bicycles. I pedalled along the flat coastal road to Anse Source D’Argent, hailed as one of the most photographed beaches in the world. What makes it more Instagrammable than the usual combo of golden sand, clear water and lush palms are its huge granite boulders, tempting the agile to climb up for a selfie.

Unesco rates the Seychelles as a global biodiversity hotspot, with the world’s largest populations of several seabirds, a high diversity of cetaceans including breeding habitats, the only dugong population in the Indian Ocean, and abundant marine life including turtles, sharks, invertebrates and more than 1,000 fish species.

The conservation of all this is supported from the top, with a Ministry of Environment, Energy and Climate Change, as well as multiple non-profit organisations protecting its plants, animals and seas. In 2020, the country hit its target of declaring 30% of its ocean territory as a Marine Protected Area.

Laws ban anyone from building within 25m of the high tide line, or from using sunbeds on the sand to prevent erosion, says John Narin, sales manager of the Constance Ephelia hotel on Mahé. The Ephelia straddles a spur of land that juts into Port Launay Marine Park, but the rooms aren’t described as having a sea view, because if palm trees or colourful hibiscus bushes are blocking your view, they won’t be cut down.

Constance Hotels and Resorts have made a commitment to sustainable tourism with initiatives including slashing their use of plastic, a mangrove reforestation programme, and desalination systems to filter seawater for use around their properties.

My base on Praslin was the Constance Lemuria hotel, which boasts its own turtle manager, Robert Matombe, to protect the green and hawksbill turtles that nest on its beaches. “The first priority for the Seychelles is conservation,” Matombe says. “There are living creatures everywhere and it’s a small world – we need to share it.”

His eco-hut is open to guests all day, with information boards about the wildlife and the fish you’ll see while snorkelling. He’s fascinating to chat to, describing how green turtles breed all year round and will beach to lay their eggs at night at any time of year, while Hawksbills beach during the day from October to February.

Outside the water they have blurry vision, so if a turtle beaches near you, stand still and it won’t notice you, he says. But if you startle it with a sudden movement, it will head for the sea and never dare to return. A turtle will mate once then lay up to 1,000 eggs in batches, making return visits every fortnight to lay 200 eggs each time. It’s all so exhausting that they only reproduce every two years.

Matombe patrols the beaches every morning, noon and evening, and spends the night there if he’s expecting a turtle to return, to protect it from poachers. The eggs are buried about 50cm deep and hatch between 56 and 72 days later. But if its rained a lot the sand becomes too heavy for the hatchlings to break free, so after 72 days Matombe digs them out.

The eggs only hatch at night when the sand is cool, and the temperature of the nest determines whether the turtles are male or female. At the moment the births are heavily skewed to females because global warming is raising the temperatures. Since the hatchlings find the sea by its luminescence, the Lemurai has removed all the lights around the nesting beaches so the babies don’t crawl towards them by accident.

I didn’t see any turtles when I snorkelled, but I swam amongst fanciful fish of bright blue and yellow; boxy dotted fish, madly striped and swirled, and dozens of angel fish. There are sea urchins too, waiting to spike careless feet. But some of the coral is bleached, and only the more robust, less delicate varieties are thriving.

“Climate change and global warming is making the bleaching more severe, so the coral reefs aren’t as diverse as they used to be,” says Chris Mason-Parker, CEO of the Marine Conservation Society Seychelles (MCSS). “It’s fairly bad in terms of mortality, especially for the pretty branched versions. The ones surviving are the rounder, less exotic looking types.”

The MCSS runs a reef restoration project in St Ann Island, with a nursery where they transplant living coral onto frames made of rope or metal. Once the coral takes hold, the frame is sunk in a reef to restore the damaged areas. “Seychelles is very environmentally-focused and prides itself on its wildlife,” Mason-Parker says. “Hopefully, increasing the amount of coral will bring back the fish as well, and improve the livelihoods of people who use the marine parks, like glass-bottom boat operators and hotels, so it will also be good for tourism.”

The MCSS also protects a species of terrapin that’s only found in the Seychelles, by tagging and monitoring them to get an idea of which areas they inhabit. It also runs a turtle monitoring programme, monitoring the critically endangered hawksbills by using software that lets them identify the individuals from their shell patterns.

Mason-Parker believes it’s important to work with hotels and their guests wherever possible, to highlight issues like climate change and over-fishing. “We’re trying to provide more information so they don’t just feel like they are on holiday, but they’re learning something in a fun way and understanding how as individuals we can reduce our impact and how our individual behaviour can affect things.”

At Beau Vallon, a popular holiday spot on Mahé, guests from Fisherman’s Cove hotel can join guided snorkelling trails to see how the reef is being restored. While the MCSS protects most marine life, it’s working to remove one particularly nasty creature – the crown-of-thorns (Acanthaster planci), a large, thorned starfish that hunts in the shallow reefs. This is a freak-show starfish, with up to 23 arms that can all regrow, covered with poisonous spines. These carnivorous predators can reach up to 80cm wide, and feed on live coral, sponges and other organisms.

Reefs that are already bleached because climate change is heating up the oceans stand less chance of recovering if these starfish devour any new growth. To help the reef at Fisherman’s Cove recover, the team is removing crown-of-thorns starfish from the reef, and hotel guests can get involved. If they tread carefully, of course.

Lesley Stones was a guest of Constance Hotels & Resorts (www.constancehotels.com) and the Seychelles Tourism Board (www.seychelles.travel)

Click HERE to read this in the latest Responsible Traveller Mag